©2023Stuart Campbell

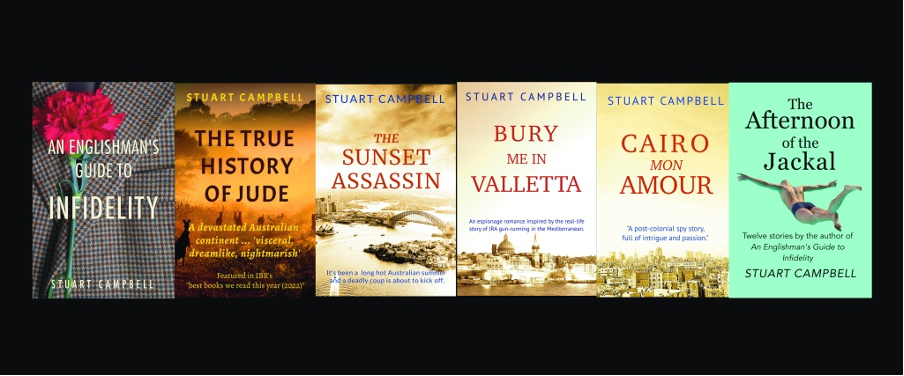

This short story was written for my Free Shorts project, which culminated in a twelve-story collection entitled The Afternoon of the Jackal. In 2025, I’m releasing one of the stories each month free on my website. Happy reading, and please leave a comment to let me know if you enjoy my work.

***

Vernon the concierge opened the glass entrance doors from the street into the marble foyer. “Good evening, Ma’am. It’s a warm one.”

I asked after his daughter – she’d been unwell – and turned into the mail room.

There was a man with his back to me, busy with his letters. My phone beeped. I looked down to check a message I’d been expecting. When I looked up, the man was leaving. He glanced back briefly and nodded. Elegant, good-looking, around my age.

But there was a letter on the floor. He must have dropped it. I picked it up and read the return address: J. P. French, Apartment 22W1. My new neighbour. The return address was a fine art dealer. I slipped the letter into J. P. French’s mailbox and took the lift to Level 22. I needed to say hello to my cat, get out of my dress and office shoes, and pour myself a cold prosecco.

In the apartment, all signs of Martin were gone: The jacket on the hallstand, the leather one he’d bought when we went to Marseille; his books, toothbrush and after-shave, clothes. And his presence was gone – always bigger than his person, a Martin who filled the room with his pacing, his intricately expressive hand gestures, and the constant cross-currents of opinions and proposals: An exhausting man, who sucked everybody into his orbit until they spun like tiny moons around his radiance.

Of course, the students adored him: A professor and department head, still bookishly good-looking at fifty, a virtuoso of the enigmatic smile. He’d been my partner for the past six years, during which time he’d apparently screwed half the Political Science department. Gone three days now, on extended leave after an enquiry into his conduct. I’d kicked him out on my fortieth birthday.

And I’d kicked myself out of his orbit.

I took the glass of prosecco onto the balcony. A cruise ship in the harbour glowed bone-white, and the ferries bobbed and twinkled in the dusk. A clinking sound made me look around: A pair of hands resting on the rail of the next balcony holding a glass of red wine, the fingers of one delicately caressing the stem of the glass in the other. A man’s hands.

My new neighbour, J.P. French. What are you like, I wondered? I thought back to the mail room encounter. Had I sensed a diffidence – or perhaps vulnerability – in that quick nod?

I fetched the prosecco and poured myself another glass.

James Patrick French stood on the balcony and read the letter again. He’d accept the invitation of course, but fretted about how he’d get through the evening. He’d never been good at socialising. Clubs, groups, societies, dinner parties, gallery cocktail parties like this one – he’d never felt right making small talk with strangers. And it was worse when the people you met at such places were so effortlessly gregarious. It wasn’t as if he were short of ideas or things to chat about. He had subscriptions to the opera and to a couple of theatres, read The Guardian online, travelled to Europe for a month each year. He could ‘work a room’ as his fellow art dealers put it, as long as the conversation was about provenance, Chinese porcelain, or the Heidelberg school of painting. But put him at a dinner table with a stranger on each side, and James French was as much company as an Art Deco vase.

These social events had been tolerable when his wife was still with him. She’d cajole him to the point where he could stitch on a smile and embroider some clever remarks to keep the chitchat going. But there were so many ways in which they were incompatible. “You’re a good man, James,” she’d said on the day he moved out. “There’s a woman out there somewhere who’ll chime with you. I can’t picture her, to be honest, but it surely isn’t me.”

With these thoughts in mind, he poured himself another glass of Shiraz and stood gazing at the stream of cars crossing the harbour twenty stories below. He didn’t miss his ex-wife, but after two years on his own he still missed the presence of another human being in his home. His new apartment building, he’d been told before he bought it, was ‘sociable but not too chummy’. The residents all knew each other. There were social activities, but ‘no pressure to join in’. It had sounded like an improvement on the inner-city terrace where, for two years, he’d spied his neighbours three or four times without exchanging a word.

This was the time of day – six or seven in the evening – when his social predicament turned to a nagging ache, the time of day when he sought company, but not too much.

He picked up a paperback, took the lift to the marble lobby and nodded to the concierge.

“Out for dinner, Sir?”

“Yes, I am. It’s Vernon, isn’t it? Any suggestions?”

“Well, Sir. If you’re happy with something casual, there’s the Casa Venezia just along to the left. Then there’s the pub on the corner.”

“How’s the food at the Casa Venezia?”

“Very good, I’m told. Actually, if you prefer not to dine alone, a group of our gentlemen have just headed there. If you tell them you’re new to the building, they’ll be very welcoming. They’re always looking for tennis partners, by the way.”

“Really?” James suppressed a squirm of mental discomfort at the thought of coping with a group of strangers. But it had to be faced. It was that or share dinner with his paperback.

The evening air was warm, heavy with an impending summer storm. James walked past the Casa Venezia and made for the pub. It was a gastro-type establishment selling craft beers, but there wasn’t a square foot of space among the yelling office workers letting off corporate steam.

Back at the Casa Venezia, he peered inside without crossing the threshold. There was nobody he recognised except a couple in their sixties who he vaguely recalled from the apartment building. They almost certainly spotted him but made a show of being exclusively engrossed in their conversation. In the far corner, five or six professional-looking men were studying the menu. James went through a mental calming exercise he had read about on the internet. He rehearsed his opening gambit: Something on the lines of, “Hello, Vernon said you might be looking for a tennis partner.” No, that was senseless. You didn’t walk up to a bunch of strangers in a restaurant and propose a sporting rendezvous. What about, “Evening, gents. I’m new to the building. Mind if I join you?” But ‘gents’ – too jaunty, too casually ironic? Perhaps ‘Hi’. Yes, ‘Hi’, the universal conversation opener. But wait: One of the professional men had given him a casual wave. He’d been recognised. The man with the wave leaned in to make a remark, and his fellows looked up at James with welcoming smiles. He raised his hand to acknowledge them, but hesitated at the sound of a voice behind him.

“Aren’t you my new neighbour?”

He turned. It was a woman. Smart, pretty, around his age. “I’m sorry,” James said. “Have we met?”

“Not exactly, unless you include under water.” He looked at her. Nothing registered.

“Butterfly,” she said. She was attractive, not unlike his ex-wife.

He remembered: The lap swimmers in the pool in the morning. For the last week there had been a lithe woman performing professional-looking butterfly stroke and elegant tumble turns. He’d quickly learned that pool etiquette demanded that unacquainted swimmers acknowledge each other only faintly through their goggles – a nod if two swimmers happened to stop for a rest, a faraway look in the opposite direction when the stranger stepped out of the pool. He hadn’t managed to see her face – just glimpsed the trim body as he turned to breathe between strokes, stole a glance at her when she climbed out of the water.

“Butterfly,” James said. “Of course.” He was trapped between the woman and the expectant faces of the professional men.

“I’m in apartment 22W2. I’m Jane,” she said, offering her hand. She wasn’t like his ex-wife, after all. There seemed to be a depth of warmth and complexity in her expression, and something else that he couldn’t put his finger on.

As he searched for some appropriate words, the street was lit up with a flash of white light followed by a crash of thunder and a sudden blanket of rain. He looked down at the outstretched hand, gently took the fingers in his. He felt a rare confidence.

“James French. Will you join me for dinner, Jane?”

PART II

I laid my business clothes on the bed and put on a kimono. The sky was darkening above the harbour. I massaged my toes on the cool tiles of the balcony. There was a discrete cough from my neighbour. The man’s hands rested on the balustrade, the fingers interlaced but tightening and loosening. A phone rang and the hands were gone. If not a diffident art specialist, then …

John Phillip French was sick of divorce lawyers. He flung the phone onto the sofa.

“Cheapskates!” The letter lay scrunched on the carpet. He’d paid a fortune for the painting by one of the ’emerging artists’ his ex-wife patronised, but the young genius had receded along with his market value before completely emerging. He’d never liked the ugly abstract picture anyway. Proper paintings had things in them you could recognise – horses, women, mountains. He’d call the bastards in the morning and insist he got half of the purchase price in the divorce settlement.

The phone rang again. He ignored it. Let them stew.

A bank of three laptops glowed in the third bedroom, the screens flickering with updates from the markets. A backdrop of office lights filled the vista from the window. There was a cruise ship on the water with a deck full of boneheads waving at bloody nobody.

He needed to focus. London would be opening soon, New York four hours later. A night’s work to do. He needed sustenance, brain food, protein, no alcohol.

Phone. Where’s the house phone? After a week in the building, he still hadn’t located the basics. There it was. Square thing, two buttons.

“Front desk, Vernon speaking. How may I help you, Mr. French?”

“I need to have a quick dinner, something decent.”

“If you like Italian, can I suggest the Casa Venezia? It’s just down the street.”

” Make me a reservation for half an hour from now.”

There was a moment’s hesitation, and then, “Of course, Sir”.

John French bit his lip; a please always helps, his ex-wife was always telling him. Actually, the only sensible thing she’d ever said.

He blasted himself in the shower, first scalding hot, then heart-shocking cold. Towelling himself in front of the mirror, he appraised his body: Still taut, no flab. A woman would be lucky …

The image of the woman in the pool intruded, and he felt a stirring between his thighs. Attractive. The wrong side of thirty but the right bloody side of forty. He refocussed on his immediate needs. She’d keep for now.

Shave. Splash of something – who cared what, but it was expensive. Rip linen shirt from laundry wrapping, choose from six pairs of chinos. Gel hair.

He exited the lobby lift and turned into the mail room, where a woman was shuffling her letters. Quick appraisal: Hot. No, very hot. The pool woman. No question about that rear end. She brushed past him and he caught a draught of something sexy and expensive. She’d dropped a letter. Name: Jane Lestrange. No sender. Apartment next to his. He put it in her box. He followed her out but the guy on the front desk was already closing the glass door as she turned into the street.

The concierge returned to his desk. John French raised an eyebrow and waited. The guy stepped out and swung the glass door, not for him but to admit an elderly lady coming in. Remember your manners, John. The stock market’s not the centre of the universe. Bloody hard to remember, though.

“Good evening, Vincent.”

“It’s Vernon, Sir.” The concierge held the door open for John French. “The Casa Venezia’s just a few steps along the street, Sir.”

It was hot, sweaty hot. He could smell his fresh man smell in the linen shirt mingling with whatever he’d splashed on. Powerful. Bloody intoxicating for a woman.

She was ten metres ahead of him, slowing by the Casa Venezia. She was inside now, and he was almost behind her. The sky cracked and raindrops like hot jellyfish slapped the pavement. The maître was shaking his head. John French heard him say, “Every table is booked, Ma’am”. The woman turned away. John French said, “I’ve got a table. The lady can share with me. Find an extra chair”.

Christ, she was a stunner. He glanced at his watch. An hour and a half before London opened. You could do a lot in an hour and a half.

“Thanks,” she said. “My name’s Jane.”

“Tarzan,” he said, “but you can call me John.”

PART III

Damn Martin. He’d phoned, begging to meet me for lunch. I told him to call up one of his students if he wanted a screw. He left messages in the afternoon. When I got home, I switched my phone to silent. I needed a drink – a big drink. There was no prosecco, but Martin had left half a bottle of Scotch in the pantry. I filled half a tumbler and stepped outside. Nobody next door. I clinked my glass on the balustrade.

The hands appeared, loosely linked at the fingertips. I leaned over the balcony to see better. One of the fingers was stained – blue, black? Or was it just a shadow? If not a frantic stockbroker, perhaps …

Jeremy Preston French stood before the picture window and drank in the view. No, he gulped it, slurped it, savoured its whole and its parts. Toy cars in their thousands in a stream of light and sparkle swept over the harbour. A bone-white cruise ship crouched against a darkening sky of inky greens and burnt apricot.

He’d painted the harbour many times, but this was a new angle. The gravid storm clouds to the north merged into the dusk, and a single dash of tropical rain flicked across the window. Slitting his eyes, Jeremy French considered how he might represent the streaked drops in paint.

He turned away and scanned the instructions his brother had left. Typical of Ken to compile an instruction manual: Lights, heating, air con, kitchen gadgets, carpet spot cleaner, kitty litter … it went on for five pages. The straight-down-the-middle brother, the careful one.

“I’ll see you in three months”, Ken had said with a final worried look at the plush cream carpet.

“Don’t worry. I’ll just be sleeping here. No painting.”

“And looking after Ludwig.”

“Relax, Ken. Cat food in, cat poo out, once a day.”

“You forgot water. When they eat dry food …”

“Enjoy Japan, Ken.”

Three months out of the studio: A holiday from his stale couch and the take-away containers and empties, and an exploratory journey into the world of the people who bought his work. It would be a chance to get under their skins, feel what they felt, understand why everybody wanted a Jeremy French on their wall.

Or used to want a Jeremy French on their wall.

The scrunched letter was in his pocket. The gallery wanted the wall space. Words honed and honeyed: ‘… despite your established reputation … increasing demand for emerging talents … need to curtail your exhibition … regretfully … ‘

He pondered his dilemma: Face the facts, French. You’ve got to find a new direction before you drop off the market altogether. Your work is dated. Derivative, some are saying: A retreat to a comfortable and undemanding abstract expressionism, a vacuous homage to Jules Olitski, the smug reviewer had written. Jeremy French’s face flushed at the memory of the coffee shop interview with the twenty two-year old media studies graduate. “Well, let’s move on, will we?” the primping pipsqueak sneered as Jeremy struggled to recall what an Olitski might look like.

Over the creative hill at forty-five. He cringed. But if he couldn’t fire up the crucible of his youth, he’d put his energy into being entrepreneurial, analytic. Work out what the punters wanted on the walls of their lounge rooms and their corporate HQ foyers. Work it out and paint it.

He poured a glass of Ken’s pricey-looking cabernet sauvignon and took it onto the balcony. There was a sharp smack as something hit the picture window beside him. It was a bird, a black and white thing, dazed on the tiles and gazing up with an unfocussed eye. One scaly foot jerked spastically. Jeremy crouched over the animal, transfixed by the tiny theatre before him: The backdrop of city lights, the leaden air, the struggling bird, Ludwig the cat frozen in orb-eyed alarm.

He was seized by a moment of exquisite connection with his soul, a spiritual charge, a sensual urge, a raw need to hold this moment in his senses. To paint it.

But the bird hopped to its feet and flew into the apartment, hitting an open cabinet of their late mother’s porcelain miniatures that scattered in broken pieces on a glass table. Ludwig leapt at the creature, which released a stream of shit on the carpet and flew out of the window. Jeremy jerked to avoid the bird and toppled over, spilling the wine in a star-shaped splash on top of the ash-coloured shit.

He surveyed the mess: Stuff, objects, things. All cleanable, replaceable. He surveyed the paintings on Ken’s walls: Safe, investment grade, boring. And there! There, nestled beside a picture of rustic farmers, was one of his smaller works: Safe, boring, and probably dropping in value.

No, bollocks to the punters. He was an artist, not a paint-to-order picture maker. He’d do what his heart had been telling him these last few months: Buy a one-way ticket. Go and paint in Turkey or Cambodia or Morocco, far from the café and film festival set who the galleries pandered to. Do something impulsive. Give his unsold works to charity. Learn to swim butterfly. Ask the first good-looking woman he met to come away with him.

But in the meantime, he was famished. There was a place down the street that Ken had taken him to. Italian, Spanish?

In the lobby, a woman was chatting to the concierge. Jeremy took in the scene: The woman gesticulating with long fingers, giving the old man an ironic grin as if they had shared an old joke one time too many. And the concierge, leaning back with his belly straining under the uniform waistcoat, artless wisdom in his crinkled smile.

The woman turned to face Jeremy.

“Aren’t you my new neighbour?” Her expression was a meld of humour, intelligence and daring. She was what? Thirty-five, forty? A woman who’d seen a thing or two and was ready for a tad more.

“Jeremy French. Good to meet you.”

“Jeremy French the painter. Yes, of course. I’m Jane Lestrange. I bought one of your pieces for our chambers. “

“You’re a lawyer?”

“Ex-lawyer. I told them where to stick their job today.”

“Well, good on you, Jane Lestrange,” Jeremy said. “Look, are you heading out for dinner? I’ve got a proposition for you.”

PART IV

I had an arrangement on Thursday evenings to meet a group of friends at a tapas bar nearby. A couple of them were lawyers like me, one was in commercial real estate, another in media. It was a low-key place where a quintet of professional women could take a booth and chat without having to shout over a roomful of men downing beers. I might entertain them with my musings about the mysterious J.P. French.

Our usual spot was empty, and I slid onto the bench seat to wait. The waiter brought a bottle of sauvignon blanc and five glasses.

After ten minutes there was no sign of my friends. I began to message one of them, but then remembered – we’d arranged to meet on Friday this week. Not like me at all: Perhaps I’d spent too much time thinking about my neighbour.

I was immediately self-conscious: A lone woman with a bottle of wine in front of her. I topped myself up and struck an ‘I’m waiting for friends’ attitude; five minutes, and I’d go to the ladies and quietly leave on the way out.

A couple had taken the booth behind me and began whispering hoarsely. I bent over and fiddled with my phone. Their voices became louder and more urgent, the whispering abandoned, their words just audible above the mood music in the background. Almost against my will, my attention was drawn to the unseen drama, and I stared harder at the phone.

“I want you back,” the man was saying.

“What right do you have to follow me here?”

“I’m your husband, that’s what right I have.”

“I want you to keep away. Just go. Now.”

“Not until you say you’ll come back, Miriam.”

Silence.

“It won’t happen again, Miriam.”

“You’re not supposed to come near me.”

“I’m just looking for a last chance. I’m telling you, it won’t happen again.”

“Really? You’ve changed, have you? You’re scaring me. Don’t make me call for help.”

“I can change. I know I can. I’m getting advice. I’ve joined a group. Other men.”

“Please just go or I’ll phone the police.”

Silence.

“Are you listening, Jack? You broke two of my fingers last time.”

Silence.

“I’m getting up now. If you move, I’ll call for help. Don’t follow me.”

“Miriam, I love you.”

“I’m going.”

“I know where you live, Miriam.”

I sensed shuffling behind me, and then saw a woman walk swiftly past and out of the door. I leaned deeper over my phone and stabbed nonsense into the buttons. His presence in the booth behind was solid, palpable. Then he was walking past me, leaving a wake of cologne with a sharp edge of perspiration. I looked up. He turned, stopped, took a step towards my booth, thrust out his hand, and said, “I think we’re neighbours. I’m Jack French.”

If you enjoyed this story, you can find details of my books here.