This is a short extract from my novel in progress Cairo Mon Amour that deals with Ivan Zlotnik, a Soviet diplomat posted to Cairo in 1973. I built Zlotnik’s character on slivers of the biographies of numerous Soviet diplomats of the era.

This is a short extract from my novel in progress Cairo Mon Amour that deals with Ivan Zlotnik, a Soviet diplomat posted to Cairo in 1973. I built Zlotnik’s character on slivers of the biographies of numerous Soviet diplomats of the era.

The novel is partly an indirect homage to the Armenian Genocide, which explains why I chose Yerevan for Zlotnik’s epiphany.

The illustration is my Communist Party of the Soviet Union membership card holder, a souvenir from my time as a student in Moscow, when I might have bumped into Zlotnik. Tucked into the card holder is my Lenin Library card.

A big thank you to my critical mates in the Write On! group in Sydney, who gave me input into an earlier draft.

I’d love to hear your responses to this extract.

©Stuart Campbell. Please respect my intellectual property by not copying the extract. There is lots of free stuff that you can legally share elsewhere on my site.

________________________________________________________________________

“You always had it made, Ivan,” his fellow MGIMO graduates would say. It was true: Barely out of university, he had the gaudy rewards of the elite in the tiny Moscow apartment, right down to the Everley Brothers records, the Marlboro cigarettes and a Playboy magazine. But when the drinking was under way – a shot of Johnny Walker between slugs of Stolichanaya – his pals’ resentment dissolved in alcoholic comradeship, the good old Soviet way: Drink until maudlin happiness is induced, that is if unconsciousness doesn’t set in first.

It didn’t matter that Yuri grew up in an orphanage while his father was in the Gulag, or that Pyotr was the son of a diesel mechanic from Kazan. They’d all made it through MGIMO and nobody could take away a degree from the Moscow State Institute of International Relations.

Zlotnik’s MGIMO friends seldom asked about his schooldays in Washington DC, where his father had been a diplomat. As for him, he preferred not to talk about being the one who sat out the Great Patriotic War in capitalist luxury while they froze their yaytsa off and lived on crusts. But his past made a difference; Zlotnik knew the West as an insider; he knew how the West felt. And this, he knew, made him dangerous, more susceptible to blandishments from beyond the Iron Curtain, a man to be carefully watched.

His parents had taken him home to Moscow in 1949, the year that Orwell’s 1984 was published. Zlotnik wolfed the book down a week before they left. But at seventeen, his political sensitivities were too undeveloped to fit the novel into a framework that included himself – Ivan Maksimovich Zlotnik, the American-speaking Russian kid who was going home. But something from Orwell must have stuck, and then it all came unstuck thirteen years later in 1962.

His was a life cut in half, he often thought: First, the years of hope and prospect and privilege when all you did made a kind of sense, and the bits that didn’t could be explained away, even his hollow marriage to Raisa. These were the years when you could reconcile the doublethink – how clever Orwell’s term was – by never daring to imagine that Soviet power was not impregnable; when as the son of a senior diplomat you had a responsibility to uphold the might of the state and prosecute its interests in Jakarta, in Hanoi, in Sydney, in corners of the world where a MGIMO graduate repaid his debt to the people. These were the years when you practised a refined dual consciousness that allowed you to lead a life based on the precepts of the Party in the sure knowledge that communism was doomed. These were the years when you reasoned away the sick in your gut when the Hungarian and Polish uprisings were crushed.

And then 1962, the height of Khrushchev’s thaw: One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was in the Moscow bookshops, there for all to read uncensored from cover to to cover, not chopped up in bits of samizdat passed illegally from hand to hand; the Gulag was exposed in all its grinding, petty, bureaucratic cruelty. In May he took a copy to Yerevan, where he was sent to prepare a propaganda article on the removal of Stalin’s statue and the installation of the Mother Armenia monument. But his real job was to collect intelligence on dissidents in the small Russian community who lived among the Armenian majority.

The day before he left he met with his wife Raisa, who was passing through Moscow. She told him that her temporary posting to the hospital in Nizhniy Novgorod had been made permanent: A promotion, not to be turned down. They would get together when they could. He’d loved her, he thought, at the beginning. But she was a doctor, he a diplomat. Their futures belonged to the state, not to themselves.

***

Zlotnik was seduced by Yerevan: The dignified self-sufficiency of the people, the stubborn uniqueness of the culture, the resistance to having their Armyanskaya Sovietskaya Respublika swamped by Russians as all the other ethnic satellites were. It was balmy springtime, the wine was good, and the women were comely. He carefully read Denisovich in his hotel room with faint echoes of Orwell’s 1984 resonating with Solzhenistyn’s words. And something in his head – or was it his heart? – came unstuck.

For the next few days he suffered anxiety and shapeless unease. One night he downed a bottle of Armenian konyak and stood on his balcony drinking in the balm of spicy air that blew across the slopes clad with grape vines and citrus. Mount Ararat was fifty kilometres to the south inside Turkey, invisible but palpably sacred in the dark. Later, he often thought, the second half of his life began that night when he heard footsteps below his window. He looked down and a young, dark woman of astonishing beauty called up to him in Armenian from the floodlit car park.

“Sorry, don’t understand,” he mumbled stupidly in Russian.

She was perhaps a little younger than his twenty nine years, dark eyes, pale skin, dressed in a flouncy black dress and carrying a violin case.

“Did you see a car around here? A black Gaz? It’s my lift home.”

“Sorry comrade, I’ve been here all night.”

“Thanks comrade, perhaps I’ll take the tram,” she said, but then a pair of lights appeared on the road outside the hotel and she turned away.

“Before you go,” Zlotnik called out. “Where are you playing?”

She turned and he watched, charmed, as the taffeta dress swirled: “I’m playing in Anoush. At the Spendiarian Theatre. Come and see.”

The next night he traded a favour to get a ticket. Anoush, it turned out, was considered Armenia’s national opera. He was overwhelmed by the majestic gravity of the performance, by the unsettling fusion of oriental and western themes and cadences. He understood nothing of the text, but during the finale he put his head in his hands and silently cried for the loss of the first half of his life. Something had come unstuck, and he would never again be able to reconcile the doublethink; damn Orwell and his word!

In the morning he was recalled to Moscow to take up the second half – the equivocal, duplicitous, dissimulating half – of his life.

©Stuart Campbell

______________________________________________________________________

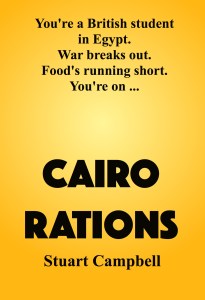

Buy Stuart Campbell’s books in paperback and ebook on Amazon by clicking on these title links:

An Englishman’s Guide to Infidelity

The Play’s the Thing

Cairo Rations is still #1 in its Amazon category and still free! In fact, it’s permanently free on Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble and Kobo. Today’s stats:

Cairo Rations is still #1 in its Amazon category and still free! In fact, it’s permanently free on Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble and Kobo. Today’s stats: