When a slick email arrived congratulating me on my ‘literary achievements’, some pleasure centre in my brain briefly glowed. Reading on, I found the standard list of offerings: Enhanced SEO, exposure on Goodreads, engagement with influencers, etc. I’m sure most fiction authors endure a similar blizzard of unsolicited offers to help sell books; in fact I suspect that more money is made in the author support business than the author business.

When a second email arrived the next day, I took a good look at both communications: They both referenced a number of my titles, threw in key plot motifs, mentioned main characters, and wrapped up the whole piece with lavish praise. ‘Wow’, I (momentarily) thought, ‘someone’s put some effort into writing this’.

The someone was apparently an opaque email address and bland name – no other details. The actual someone was clearly a Generative AI setup that has scraped my book blurbs off the internet and tipped them into a copywriting blender. A similar non-human email arrived two days later, this time from a company with a website and the street address of a seedy premises on the fringes of a major US city that looked as if it might double up as a swingers club.

These emails could have been the reason the term ‘bottom feeding’ was coined: Fiction writing is so poorly remunerated that – from the author’s point of view – the writing industry barely deserves the term ‘industry’ at all. It staggers me that somebody can find a business niche that depends on scraping thousands and thousands of book blurbs in the hope of hitting authors willing to cough up good money for services that in my experience yield a negative ROI.

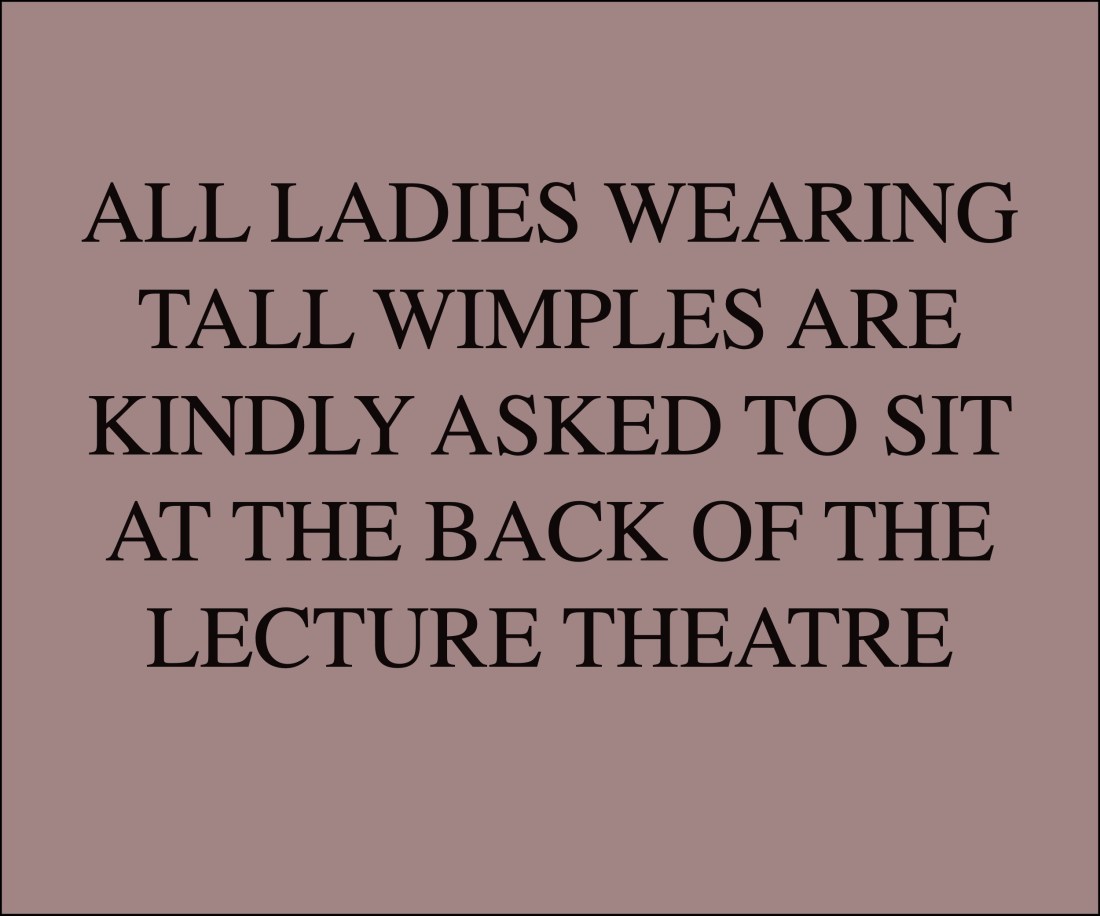

My other Generative AI encounter arose from a professional postgraduate course I recently enrolled in – fourteen years after I retired as a Pro Vice Chancellor and forty years since I was last a uni student. I was intrigued to learn that the university’s obligatory unit on academic integrity was much preoccupied with the hazards of dealing with AI in academic writing

So far, so good. Except that my second study unit entailed (a) researching a topic using a Generative AI tool, (b) researching it with my human brain, and (c) comparing the results. A quick check showed that this assessment item fulfilled a graduate attribute on understanding AI.

My human brain research wiped the floor with the GenAI version, and I managed to gleefully use the term ‘stochastic parrot’ (properly referenced) in the closing paragraph of the paper.

I remain in support of the proposal that ‘the role of the university is to resist AI, that is, to apply rigorous questioning to the idea that AI is inevitable’.