©2023Stuart Campbell

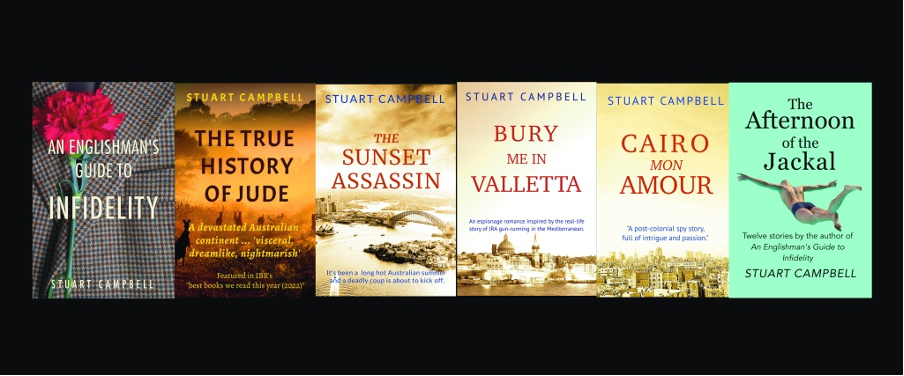

This short story was written for my Free Shorts project, which culminated in a twelve-story collection , which is itself entitled The Afternoon of the Jackal. In 2025, I’m releasing one of the stories each month free on my website. Happy reading, and please leave a comment to let me know if you enjoy my work.

***

“Those jeans look bloomin’ ridiculous,” Dad said. This from an overweight middle-aged man in a Santa hat and a yellow T-shirt with PROUDLY MADE IN THE UK on it. Okay, so maybe that extra rip around the butt was a bit too revealing. I offered to carry the wine when we got out of the Kluger, and let the two-bottle cooler hang over the gash in the denim. Mum went ahead bearing the bowl of home-made tabbouleh she brought every year, great-granny’s special Armenian recipe of course.

“And don’t curl that lip, Missy,” Mum said without even looking back to see my expression. Sure, I’d made a slight fuss about going to Uncle Gary’s Boxing Day barbecue. I mean, I’m sixteen next month, I’ve got a life of my own, things to do, stuff Mum and Dad wouldn’t have a clue about. And it’s so far, way up on the Northern Beaches on the other side of Sydney.

We go to our uncle’s place every Boxing Day. He’s actually called Garo, but Dad is genetically incapable of pronouncing foreign names, so he relabelled Mum and her brother years ago. Mum’s really called Serpouhi, which isn’t exactly hard to say, but Dad can only manage Sophie.

Anyway, every December 26, me and my cousins have to sit around the patio table in the heat drinking soft drinks while the adults get jolly and bang on about mortgages and TV programs and real estate prices and cholesterol and Jimmy Barnes. I’d planned to go to a party with my friends, but Dad said Uncle Gary would be hurt if I didn’t come this year, especially since his partner Derek had passed away last January.

So I did come after all, which was why I didn’t appreciate Mum’s comment because I was definitely not curling my lip. What changed my mind was the news that Uncle Gary had got married to a guy from Scotland.

Yes, married.

My cousin Ruby phoned me the week before and told me about it and how the husband was young and hot. But Uncle Gary’s old and fat, I said. Yeah, weird, Ruby said, but can we just say he’s got a larger build, you know, not f-a-t. Ruby’s studying psych at uni, and she’s always banging on about triggering words as if I’ve never heard of it.

I asked Mum and Dad about Uncle Gary over breakfast, and they said oh didn’t we mention it? No, I said with maximum offended dignity. Anyway, I said, curiosity winning over dignity, what do you guys think about it? Then they went all ‘each to his own,’ and ‘it’s not for us to judge’ but I knew they were busting to see the new crush.

Uncle Gary and Derek had been a family fixture since before I was born, and the story behind the Boxing Day barbecue (also a fixture since before I was born) was that since Mum’s brother was a bachelor and didn’t have any kids to spend the day with, we were ‘good company’ for him. Mum said ‘bachelor’ as if it was a box with a ghastly secret inside, like when people say ‘cancer’ and you have the horrors imagining tumours on their eyeballs or wherever. I remember Dad talking to a friend about Uncle Gary and them both sniggering when the friend asked if he was a confirmed bachelor. As the years went on, it gradually dawned on us kids that Gary and Derek were more than bachelors, but woe betide anyone who mentioned the ‘gay’ word to Mum. One year, my cousin Jackson – he would have been eight – asked out loud if Uncle Gary was a poof, and everyone suddenly found something loud to say: More of that lamb? Pass the Cab Sav. Goodness, it’s thirty-two degrees, usually rains over Christmas.

So this Boxing Day barbecue doubled up as the regular gathering plus the Scottish husband’s debut, not that anyone actually said that he’d be presented to the family; we just all knew. The honeymoon, we heard, had been in Goa, which was doubly weird since Uncle Gary and Derek used to drive to Noosa for their holidays, although Derek travelled overseas a lot for his work.

As we walked up the path to the front door, Mum was all fake brightness and Dad had huge armpit sweat stains. It struck me that the garden looked a bit tatty. Uncle Gary’s place was nestled in a subtropical suntrap on a cliff overlooking the beach. Derek used to keep the lush plants immaculately pruned, but now there were fat spiders hanging on webs between the yellowing leaves and gone-to-seed blooms.

The rest of the clan were there – about fifteen now that we three had arrived. I spotted Ruby chugging a beer on the back patio. She waved and nodded at the beer bottle; she’d sneak one out for me later. A stranger was turning kebabs on the barbecue – it must be a caterer, although Uncle Gary usually did the cooking himself on Boxing Day. When the guy turned and waved, I realised it was my uncle, not in his usual billowing kaftan, but shorts and a T-shirt. He must have lost thirty kilos.

Everyone seemed to be busy setting the table and avoiding looking at Uncle Gary or the back garden. So where was the Scottish hottie? Uncle Gary gave me a skinny hug while I did a recce over his shoulder – no sign.

“You’ve grown, let me see you, so beautiful.”

I did a cute pose. “And you, Uncle Gary, you’ve …”

“Shrunk,” he said, and we both laughed.

“That lamb smells good,” I said.

“I’ve done some of those English pork sausages for your dad.” We laughed again.

Ruby popped out from behind a gazebo. She flipped the tops off two beers and beckoned me onto the terrace leading to the pool on the next level.

“Look.”

We sat under the palms to watch the man sunning himself prone by the pool.

“That’s Romeo,” Ruby whispered.

“Is that his name, Romeo?”

“No, you dill. He’s Edward. Romeo’s like in Shakespeare.”

“Right, so Uncle Gary’s Juliet?”

“Shut up. He can hear us.”

The man was in perfect shape – muscular but not pumped, smooth golden skin, close, wiry black hair. He wore tiny red bathing shorts – hardly more than a G-string.

“Oh my God. What a waste.” Ruby swigged on the beer. I’d drunk half of mine too fast and was feeling slightly woozy on an empty stomach.

“Fuck, yeah,” I said, and then felt a bit stupid because Ruby had a thing about not using the f-word casually: It’s a weapon. Use it sparingly. Make it fucking count.

Uncle Gary’s Chinese lunch gong rang – another annual fixture.

Romeo stirred, turned on his back. He was brutally handsome, in his late twenties maybe.

“Don’t stare,” I whispered.

“I’m appraising.”

He looked at us both with a glassy expression and slipped into the pool, swimming rapid laps, smoothly and effortlessly like a dolphin.

We ran up the steps to the long table on the vine-covered terrace. A sea breeze took the edge off the noon heat. Mum was freshening up the tabbouleh, which was looking limp after an hour and a half on the back seat of the car.

An empty chair highlighted the new husband’s absence.

“Will I fetch Edward from the pool?” Mum asked. “I expect he’s hungry.”

Uncle Gary looked up from serving the kebabs. “He’ll be up in a minute. Just getting dressed I should say.” Ruby frowned at me. I shrugged my shoulders.

But Romeo didn’t come. The atmosphere was fragile. Mum kept looking towards the pool area. Dad attacked his British sausages and launched into a long story about the warranty on his new mower.

Gone was the jocular banter of past years. Uncle Gary used to be an architect and Derek had been a professional violinist, and they would entertain us with a ping-pong of affectionate digs and well-rehearsed anecdotes throughout the meal, with Dad trying to outdo them with lead balloon rejoinders that were so bad you wouldn’t waste breath groaning at them. The couple had been complete opposites: Derek small and dapper in crisply pressed whites and tinted glasses, Uncle Gary portly and dishevelled. They used to play really cool old school music over the outdoor sound system – jazz, I suppose. But this year it was just the clink of cutlery mixed up with people saying jeez and wow at Dad’s mower warranty story.

On the way home last year, Mum, a bit relaxed after too much prosecco, had said to Dad, “Do you think they, you know, do it?” Dad laughed: “I doubt if Gary can locate the wherewithal.” I just pretended I hadn’t heard. It’s so embarrassing when they talk about that kind of stuff. What I did know was that Derek and Uncle Gary loved each other, not like Mum and Dad, who just seem to put up with each other.

Dad’s story ended at last, and everyone stared at their plates while Mum tried to drag information out of her brother.

“Where did you and Edward meet?”

“Oh, it would have been online as far as I remember.”

Dad put on his ‘how interesting, tell us more’ face, but Mum jumped in with, “And Goa for the honeymoon? It sounds so exotic.”

“A bit more spicey than Noosa,” Dad chipped in and winked at Mum. I hate winking. It’s so gauche. Mum says Dad can’t help it because he’s English, and nobody on her side of the family ever winked because in the Armenian community they have better manners.

Uncle Gary mumbled something about having a good travel agent.

“Oh, absolutely, a good travel agent’s an absolute essential,” Mum forged on, swerving into another conversational lane. “And what does Edward do?”

“Do?”

“For a living, you know?”

“He’s looking around for an opportunity, maybe taking a course or something.”

“But did he have a job before?”

“Oh yes, definitely.”

“What job was that, darling?”

I cringed. Mum saying ‘darling’ means the thumbscrews are coming out.

“He was a dancer.”

“Did you say dancer?” Mum asked, omitting ‘not a doctor or a pharmacist?’

“Yes, a dancer?”

“What kind of dancer, Garo?”

“On cruise ships.”

Mum froze while she processed this bit of information that had no known geolocation in her world view. That’s a big difference between her generation and mine – cognitive flexibility, adaptability to new ideas.

As Mum opened her mouth, Dad jumped in. “Come on Sophie, that’s enough of the third degree. Give poor old Gary a minute to eat his lunch.”

Ruby got us back on track by telling the younger kids to sing a Christmas song, and the adults munched in gratitude. When the brats finished the first song, Ruby started them on another and the atmosphere relaxed because the adults didn’t have to talk. Then it was time for dessert and more fussing with dishes and spoons to cover up the unmentionable absence.

“Oh, here he is at last,” Uncle Gary said with a chuckle I’d never heard before, a bit like when a cute puppy jumps onto the couch. Edward appeared under the entrance to the gazebo, shiny with lotion and almost naked. Dad, who was nearest to him, jerked out of his chair, toppling it into a display of potted orchids. He scrabbled in the pots, righted them, straightened himself up, and thrust his hand out with a booming “How d’you do, Edward”. Mum’s jaw hung open. Ruby peeped at me and smirked. The kids looked up from their ice cream.

Edward ignored Dad, who looked around at us in bafflement, retrieved his chair and topped up his wineglass.

The near-naked man sat down in the empty seat, filled a bowl with pav and ice cream, and hunched over it, slurping with a fist-gripped spoon.

“Haha,” Uncle Gary said, “My diamond in the rough,” at which Mum spluttered something through her ice cream that might have had the word ‘manners’ in it.

Ruby stood up and told the little kids it was swim time and the last one in the pool was a squashed banana. She led the giggling herd out of the gazebo leaving me, Mum, Dad, Uncle Gary, and Edward behind, as well as two sets of uncles and aunts who, sensing trouble, said they were desperate for a ciggie.

With the smokers puffing away in the driveway, Edward scraped his bowl clean and burped. My phone vibrated. I peeped down. Ruby: Keep me posted.

“Well, this is a bit different,” Dad said. We all looked at Uncle Gary.

“I need to explain one or two things,” he said. “Edward, sweetheart, come over here.”

Dad made a choking noise and blew his nose.

Romeo slipped into the seat vacated by one of the smokers. He held Uncle Gary’s hand.

“You see,” my uncle went on, “Things aren’t always what they seem. I know you’re thinking about those lovely Boxing Day parties, and how Derek and I were so smart and funny and happy.”

“You were smart and funny and happy. Weren’t they?” Mum said, looking at me and Dad for agreement. I shrugged. Dad frowned.

“It was all an act.”

Romeo produced some words that sounded like “Ball make widna fract,” and Uncle Gary said, “Yes, sweet boy”.

Dad spluttered, “How was it an act?”

“I hated him. I detested Derek.”

Dad chewed a fingernail. I looked at the baba ghanoush.

“No,” Mum spluttered like a goldfish flipped out of its bowl.

Dad squared his shoulders but Uncle Gary waved his hand before he could say any more.

“Derek was cruel and controlling. He treated me like a slave. Worse than a slave.”

My parents goggled at him, making vague lip movements as if words were trying to come out but hadn’t made their minds up what they should sound like.

“But why didn’t you …”

“Why didn’t I leave, Sophie? He was clever. He made me believe my inadequacies were my fault and that without him I’d be useless and lonely. He used to bring his sleek friends here and flaunt them at me. He was always taunting me for being fat, and the more he did it, the more I ate. I was so ashamed. The kaftan was his idea. The sack of shame, he called it.”

“Well, I’ll be buggered,” Dad muttered, never lost for the wrong word. “Are you sure about all this, Gary?”

Mum waved me down to the pool, evidently fearing I was in acute moral peril. I ignored her. Another text from Ruby: He’s straight. Has to be. Just wants a spouse visa. What’s going on?

I texted under the table: It’s getting weird here.

Ruby replied: Be there in a sec.

Edward now had his arm around my uncle’s shoulder. His glassy expression had turned to deep concern and sorrow. He said something in an accent like chunks of words mixed up with garden pebbles.

Dad stood up and crossed his arms. “Sorry Gary. This isn’t making sense. You’re telling us the bloke you lived with for decades, the bloke you made a big sobbing speech about at the funeral … I mean, we knew him, he was like … y’know, someone we … “

“… liked, trusted,” Mum chipped in.

“… respected,” Dad added.

I stood up and crossed my arms. “It’s called coercive control, Dad. These people can be very manipulative.” This from the girl domestic violence expert who, half an hour ago, was emoting over Derek and Gary’s love and devotion. I’m a fast learner, you have to be in this world, and anyway we’re doing a project on domestic violence in social studies at school right now. Judging from Dad’s angry glare, I should have shut up, but I was saved by Ruby, who glided into the gazebo wearing – but only just – the tiniest bikini in Sydney.

“Edward, we didn’t get introduced properly.” She knelt next to the new hubby with face tilted to receive a social kiss, which was rewarded with the icy stare. Edward muttered more pebbly Scottish words and went back to consoling my uncle. Ruby stood up, stared around at us all completely affronted; nobody ignores Ruby. We looked back, bewildered.

“Well,” Mum said, looking at her watch.

***

On the way home in the Kluger, I put on my headphones and pretended to listen to music while Mum and Dad thrashed out a story to fit the evidence: Maybe Derek hadn’t been quite the angel they thought he was, but Gary was probably exaggerating, after all grief did strange things. Yes, they remembered that Derek could be a bit sarcastic, but then Gary gave as good as he got, well not always, there was that time he walked out on the Boxing Day lunch and didn’t come back, and Derek sniggered that he was having his period. And the kaftan and the weight, who’s to know what goes on in other people’s relationships? And especially homosexuals – after all, it can’t be the same as a woman and a man, can it? (Mum looked back to check I had the headphones on.) As for Edward, he was odd but seemed sincere, although you couldn’t understand a word he said. Takes all sorts to make a world, and it’s a fact that some Scottish people can be surly, but time would tell. If he’d got Gary to lose thirty kilos, he was worth his weight in gold for that alone. Dad thought he’d probably located his wherewithal at last, but it was so weird that a handsome chap like Edward can go off and play with the other team. Still, look at poor Ruby and the deadheads she finds on her apps, like that artsy fartsy one she’s living with, all Ned Kelly beard and quinoa and almond lattes. Mind you, it wasn’t exactly fun this year. Maybe now that Gary has Edward, they’ll go away next Boxing Day and we can do something different.

When we got home I went to my room. Ruby called.

“Did you see the look on his face when I bent over?”

“What look?” I asked.

“Male gaze on steroids. When I dropped my bag. The hungry jackal look. I tell you, he’s a fake. The evidence is in.” She made a growling noise.

“Evidence? What evidence?”

“It was an experiment, to see how he’d react. You saw his face.”

“Yeah, I suppose,” I said. An experiment? A girl dropping her bag in front of a guy?

Ruby went on, all fired up. “Maybe someone should tell Uncle Gary. He deserves to know, doesn’t he?”

I wasn’t quite sure about this, even though Ruby’s knows a lot of psych. I also felt slightly uncomfortable about the way she bent over when she pretended to drop her bag. I mean there are times when it’s OK to be a bit over the top, but the way she did it was just embarrassing with Mum and Dad and Uncle Gary all there. And then twisting around and looking straight at Edward.

“You’re probably right, Ruby. Hey, gotta go, Mum wants something.”

***

Ruby’s embarrassing performance wouldn’t shake itself from my thoughts. I lay awake that night replaying in my mind what I’d seen as we were leaving: Edward hanging back while we farewelled Uncle Gary. Dad giving Uncle Gary a giant handshake, Mum hugging her brother. Dad launching in Edward’s direction with an outstretched hand and changing his mind and retreating at the last moment. The more I replayed it, the clearer it became. They all stood around for half a minute saying, “Well, then,” and “That was lovely,” until Mum said to Dad, “Hit the road, Jack.” We all laughed, and that’s when Ruby did her thing. I remember looking towards Edward at that moment; he frowned at Ruby bent double, looked up at me and gave me a really nice wink. I felt this connection, like he was an older brother.

The bit about Ruby’s experiment was bugging me too. I mean, you might do something like that as a sort of test, but calling it an experiment seemed over the top. So I did a search and came up with Single Subject Experiments in psychology, which had nothing to do with what Ruby did, and I came to the conclusion that just because she’s doing psych at uni, she’s actually a bullshitter.

###

If you enjoyed this story, you can find details of my books here.